“Most people come to Whanganui for the three A’s: the awa, the art, and the architecture. I came searching for one man.

But there’s just one problem. He’s been dead 125 years.”

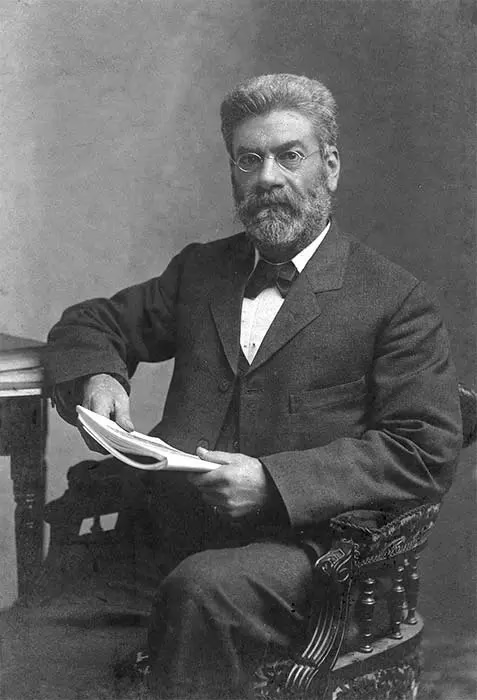

Whanganui is a city that proudly wears its history on its sleeve – evident in its Edwardian buildings, its winding river, and its vibrant creative scene. But for me, this trip wasn’t about sightseeing. It was about finding Samuel Henry Drew, my mum‘s dad‘s mum’s dad.

I’d always known he was a jeweller. Family whispers said he was “a bit of a big deal,” but no one ever explained why.

What I didn’t know until recently was that Samuel was also the founder of the Whanganui Regional Museum, a prolific collector, and a surprisingly modern thinker for a 19th-century man.

This episode of One Ancestor at a Time follows the trail he left – from taxidermied marsupials and extinct birds to letters from the leading scientists of his day. It was more than a family history lesson. It was a revelation.

From Jeweller to Gentleman Scientist

Born in England in 1844, Samuel Drew wasn’t born into science; he was apprenticed into watchmaking and jewellery, a craft that requires precision, patience, and attention to detail. These same qualities would later define his scientific collecting. After training in England, he moved to Whanganui, New Zealand, and established a jewellery business. But it was what he did outside business hours that astonished me.

Samuel was part of a 19th-century global movement of “gentleman scientists” – amateurs who made major contributions to science despite lacking formal academic credentials. He was a self-taught naturalist – an autodidact and polymath – obsessed with collecting and classifying the natural world. His house became a menagerie of specimens, eventually so overrun that it could no longer function as a family home.

He had eight children, a booming business, and somehow found time to engage in rowing, choral societies, and extensive correspondence with museums around the world.

A legacy preserved in fur, feather and ink

My visit to the Whanganui Regional Museum began with a behind-the-scenes tour led by Trish Nugent-Lyne, the museum’s Curatorial and Collections Lead (Pou Tiaki). We talked surrounded by old display cases and even older stories.

Samuel’s private collection of natural history and ethnological artifacts formed the core of the museum when it was established in 1892. The city council purchased his collection for £600 (a substantial sum at the time) with the stipulation that it remain open to the public.

Among the highlights Trish showed me:

- A marble bust of Samuel, created posthumously.

- Taxidermied specimens from his original collection, including wallabies, koalas, seals, and even his family cat.

- A thylacine (Tasmanian tiger) – now extinct and one of the most well-preserved specimens in the world. It’s a global treasure, sitting in this regional museum thanks to my ancestor’s obsession.

The museum’s storage rooms are still filled with pieces Samuel gathered: fish, birds, mammals, and oddities. We even saw a passenger pigeon, a species once abundant in North America but hunted to extinction. How did it end up here? Through Samuel’s vast international network.

The Correspondent Collector

One of the most eye-opening aspects of the tour was access to Samuel’s correspondence and scientific letters. He wasn’t working in isolation. He was part of a growing community of global thinkers, including some of New Zealand’s most respected scientists.

He traded specimens and letters with:

- Henry Suter, a Swiss-born New Zealand naturalist and malacologist.

- Frederick Wollaston Hutton, curator, professor, and one of New Zealand’s foremost geologists.

- Andreas Reischek, a controversial Austrian taxidermist and naturalist, whose legacy includes both significant scientific contributions and problematic grave-robbing practices.

In 1897, Samuel was named a Fellow of the Linnean Society—a prestigious scientific institution still active today. For a man with no formal science training, this was a serious achievement.

And he wasn’t content to keep his knowledge private. He used photographs, sketches, and even trick photography to plan museum displays. His mission was clear: bring the world to Whanganui.

A Shift In Mindset: Then vs. Now

Of course, the museum has changed since Samuel’s time. Trish explained how today’s practices involve consultation with iwi and hapū, particularly regarding taonga Māori. Where Samuel’s displays once mixed sacred and mundane artifacts together, the modern museum observes kaupapa Māori principles, such as the distinction between tapu and noa objects—even in how collections are stored.

Now, kaitiaki and whānau often determine what can be displayed or loaned. It’s a model of partnership and protection, and it stands in contrast to the encyclopedic accumulation mindset of colonial-era collectors like Samuel.

Still, the DNA of his vision is very much alive: a desire to educate, to engage, to spark wonder. While Samuel and his generation may not have understood the values we hold today, I admire his commitment to give his life’s work to a community for the sake of learning.

Final Resting Place

Samuel Drew died suddenly at the age of 57. Fittingly, he died while at work. He is buried at Heads Road Cemetery in Whanganui, alongside his wife and one of their daughters. It’s a quiet place, unremarkable at a glance – until you realize who lies beneath.

Walking In His Footsteps

For me, this trip wasn’t just about gathering facts. It was about connecting threads, walking the same streets, seeing up close the institution he helped create, and learning what became of it after his untimely death.

I didn’t expect to find so much of myself in this man. But I did. And I hope, in watching the episode or reading this post, you find something of yourself in him too.

Want to learn more?

Here are some links to continue your own search for knowledge:

- Discover Whanganui – Travel, heritage, and attractions

- Whanganui Regional Museum – Plan your visit

- Samuel Henry Drew – Biography on Te Ara

- The Graverobber: Andreas Reischek – RNZ’s ‘Black Sheep’ podcast

- Linnean Society of London – One of the world’s oldest scientific societies

- FW Hutton and Henry Suter – Fellow scientists Samuel corresponded with

Watch the Full Episode

Subscribe & Join the Journey

Want to follow along as we trace our whakapapa, one story at a time?

Visit OneAncestor.co and subscribe for updates, behind-the-scenes stories, and upcoming episodes.

Coming soon: Samoa

In the next episode, we travel sideways on my family tree, to the beautiful islands of Samoa, where my wife comes from. Culture, identity, and belonging in the islands. Stay tuned.